Nexus User Scripts

Users interact with Nexus by writing a Python script that often resembles an input file. A Nexus user script typically consists of six main sections, as described below:

- Nexus imports:

functions unique to Nexus are drawn into the user environment.

- Nexus settings:

specify machine information and configure the runtime behavior of Nexus.

- Physical system specification:

create a data description of the physical system. Generate a crystal structure or import one from an external data file. Physical system details can be shared among many simulations.

- Workflow specification:

describe the simulations to be performed. Link simulations together by their data dependencies to form workflows.

- Workflow execution:

pass control to Nexus for active workflow management. Simulation input files are generated, jobs are submitted and monitored, output files are collected and preprocessed for later analysis.

- Data analysis:

control returns to the user to extract preprocessed simulation output data for further analysis.

Each of the six input sections is the subject of lengthier discussion: Nexus imports, Nexus settings: global state and user-specific information, Physical system specification, Workflow specification, Workflow execution, and Data analysis. These sections are also illustrated in the abbreviated example script below. For more complete examples and further discussion, please refer to the user walkthroughs in Complete Examples.

Nexus imports

Each script begins with imports from the main Nexus module. Items imported include the interface to provide settings to Nexus, helper functions to make objects representing atomic structures or simulations of particular types (e.g. QMCPACK or VASP), and the interface to provide simulation workflows to Nexus for active management.

The import of all Nexus components is accomplished with the brief

“from nexus import *”. Each component can also be imported

separately by name, as in the example below.

from nexus import settings # Nexus settings function

from nexus import generate_physical_system # for creating atomic structures

from nexus import generate_pwscf # for creating PWSCF sim. objects

from nexus import Job # for creating job objects

from nexus import run_project # for active workflow management

This has the advantage of avoided unwanted namespace collisions with user defined variables. The major Nexus components available for import are listed in Table 1.

component |

description |

|---|---|

|

Alter runtime behavior. Provide machine information. |

|

Create atomic structure including electronic information. |

|

Create atomic structure without electronic information. |

|

Create generic simulation object. |

|

Create PWSCF simulation object. |

|

Create VASP simulation object. |

|

Create GAMESS simulation object. |

|

Create QMCPACK simulation object. |

|

Create SQD simulation object. |

|

Create generic input file object. |

|

Create generic input file object representing multiple files. |

|

Create PWSCF input file object. |

|

Create VASP input file object. |

|

Create GAMESS input file object. |

|

Create QMCPACK input file object. |

|

Create SQD input file object. |

|

Provide job information for simulation run. |

|

Initiate active workflow management. |

|

Generic container object. Store inputs for later use. |

Nexus settings: global state and user-specific information

Following imports, the next section of a Nexus script is dedicated to

providing information regarding the local machine, the location of

various files, and the desired runtime behavior. This information is

communicated to Nexus through the settings function. To make

settings available in your project script, use the following import

statement:

from nexus import settings

In most cases, it is sufficient to supply only four pieces of

information through the settings function: whether to run all jobs

or just create the input files, how often to check jobs for completion,

the location of pseudopotential files, and a description of the local

machine.

settings(

generate_only = True, # only write input files, do not run

sleep = 3, # check on jobs every 3 seconds

pseudo_dir = './pseudopotentials', # path to PP file collection

machine = 'ws8' # local machine is an 8 core workstation

)

A few additional parameters are available in settings to control

where runs are performed, where output data is gathered, and whether to

print job status information. More detailed information about machines

can be provided, such as allocation account numbers, filesystem

structure, and where executables are located.

settings(

status_only = True, # only show job status, do not write or run

generate_only = True, # only write input files, do not run

sleep = 3, # check on jobs every 3 seconds

pseudo_dir = './pseudopotentials', # path to PP file collection

runs = '', # base path for runs is local directory

results = '/home/jtk/results/', # light output data copied elsewhere

machine = 'titan', # Titan supercomputer

account = 'ABC123', # user account number

)

Physical system specification

After providing settings information, the user often defines the atomic structure to be studied (whether generated or read in). The same structure can be used to form input to various simulations (e.g. DFT and QMC) performed on the same system. The examples below illustrate the main options for structure input.

Read structure from a file

dia16 = generate_physical_system(

structure = './dia16.POSCAR', # load a POSCAR file

C = 4 # pseudo-carbon (4 electrons)

)

Generate structure directly

dia16 = generate_physical_system(

lattice = 'cubic', # cubic lattice

cell = 'primitive', # primitive cell

centering = 'F', # face-centered

constants = 3.57, # a = 3.57

units = 'A', # Angstrom units

atoms = 'C', # monoatomic C crystal

basis = [[0,0,0], # basis vectors

[.25,.25,.25]], # in lattice units

tiling = (2,2,2), # tile from 2 to 16 atom cell

C = 4 # pseudo-carbon (4 electrons)

)

Provide cell, elements, and positions explicitly:

dia16 = generate_physical_system(

units = 'A', # Angstrom units

axes = [[1.785,1.785,0. ], # cell axes

[0. ,1.785,1.785],

[1.785,0. ,1.785]],

elem = ['C','C'], # atom labels

pos = [[0. ,0. ,0. ], # atomic positions

[0.8925,0.8925,0.8925]],

tiling = (2,2,2), # tile from 2 to 16 atom cell

kgrid = (4,4,4), # 4 by 4 by 4 k-point grid

kshift = (0,0,0), # centered at gamma

C = 4 # pseudo-carbon (4 electrons)

)

In each of these cases, the text “C = 4” refers to the number of

electrons in the valence for a particular element. Here a

pseudopotential is being used for carbon and so it effectively has four

valence electrons. One line like this should be included for each

element in the structure.

Workflow specification

The next section in a Nexus user script is the specification of simulation workflows. This stage can be logically decomposed into two sub-stages: (1) specifying inputs to each simulation individually, and (2) specifying the data dependencies between simulations.

Generating simulation objects

Simulation objects are created through calls to “generate_xxxxxx”

functions, where “xxxxxx” represents the name of a particular

simulation code, such as pwscf, vasp, or qmcpack. Each

generate function shares certain inputs, such as the path where the

simulation will be performed, computational resources required by the

simulation job, an identifier to differentiate between simulations (must

be unique only for simulations occurring in the same directory), and the

atomic/electronic structure to simulate:

relax = generate_pwscf(

identifier = 'relax', # identifier for the run

path = 'diamond/relax', # perform run at this location

job = Job(cores=16,app='pw.x'), # run on 16 cores using pw.x executable

system = dia16, # 16 atom diamond cell made earlier

pseudos = ['C.BFD.upf'], # pseudopotential file

files = [], # any other files to be copied in

... # PWSCF-specific inputs follow

)

The simulation objects created in this way are just data. They represent requests for particular simulations to be carried out at a later time. No simulation runs are actually performed during the creation of these objects. A basic example of generation input for each of the four major codes currently supported by Nexus is given below.

Quantum Espresso (PWSCF) generation:

scf = generate_pwscf(

identifier = 'scf',

path = 'diamond/scf',

job = scf_job,

system = dia16,

pseudos = ['C.BFD.upf'],

input_type = 'generic',

calculation = 'scf',

input_dft = 'lda',

ecutwfc = 75,

conv_thr = 1e-7,

kgrid = (2,2,2),

kshift = (0,0,0),

)

The keywords calculation, input_dft, ecutwfc, and

conv_thr will be familiar to the casual user of PWSCF. Any input

keyword that normally appears as part of a namelist in PWSCF input can

be directly supplied here. The generate_pwscf function, like most of

the others, actually takes an arbitrary number of keyword arguments.

These are later screened against known inputs to PWSCF to avoid errors.

The kgrid and kshift inputs inform the KPOINTS card in the

PWSCF input file, overriding any similar information provided in

generate_physical_system.

VASP generation:

relax = generate_vasp(

identifier = 'relax',

path = 'diamond/relax',

job = relax_job,

system = dia16,

pseudos = ['C.POTCAR'],

input_type = 'generic',

istart = 0,

icharg = 2,

encut = 450,

nsw = 5,

ibrion = 2,

isif = 2,

kcenter = 'monkhorst',

kgrid = (2,2,2),

kshift = (0,0,0),

)

Similar to generate_pwscf, generate_vasp accepts an arbitrary

number of keyword arguments and any VASP input file keyword is accepted

(the VASP keywords provided here are istart, icharg, encut,

nsw, ibrion, and isif). The kcenter, kgrid, and

kshift keywords are used to form the KPOINTS input file.

Pseudopotentials provided through the pseudos keyword will fused

into a single POTCAR file following the order of the atoms created

by generate_physical_system.

GAMESS generation:

uhf = generate_gamess(

identifier = 'uhf',

path = 'water/uhf',

job = Job(cores=16,app='gamess.x'),

system = h2o,

pseudos = [H.BFD.gms,O.BFD.gms],

symmetry = 'Cnv 2',

scftyp = 'uhf',

runtyp = 'energy',

ispher = 1,

exetyp = 'run',

maxit = 200,

memory = 150000000,

guess = 'hcore',

)

The generate_gamess function also accepts arbitrary GAMESS keywords

(symmetry, scftyp, runtyp, ispher, exetyp,

maxit, memory, and guess here). The pseudopotential files

H.BFD.gms and O.BFD.gms include the gaussian basis sets as well

as the pseudopotential channels (the two parts are just concatenated

into the same file, commented lines are properly ignored). Nexus drives

the GAMESS executable (gamess.x here) directly without the

intermediate rungms script as is often done. To do this, the

ericfmt keyword must be provided in settings specifying the path

to ericfmt.dat.

QMCPACK generation:

qmc = generate_qmcpack(

identifier = 'vmc',

path = 'diamond/vmc',

job = Job(cores=16,threads=4,app='qmcpack'),

input_type = 'basic',

system = dia16,

pseudos = ['C.BFD.xml'],

jastrows = [],

calculations = [

vmc(

walkers = 1,

warmupsteps = 20,

blocks = 200,

steps = 10,

substeps = 2,

timestep = .4

)

],

dependencies = (conv,'orbitals')

)

Unlike the other generate functions, generate_qmcpack takes only

selected inputs. The reason for this is that QMCPACK’s input file is

highly structured (nested XML) and cannot be directly mapped to

keyword-value pairs. The full set of allowed keywords is beyond the

scope of this section. Please refer to the user walkthroughs provided in

Complete Examples for further examples.

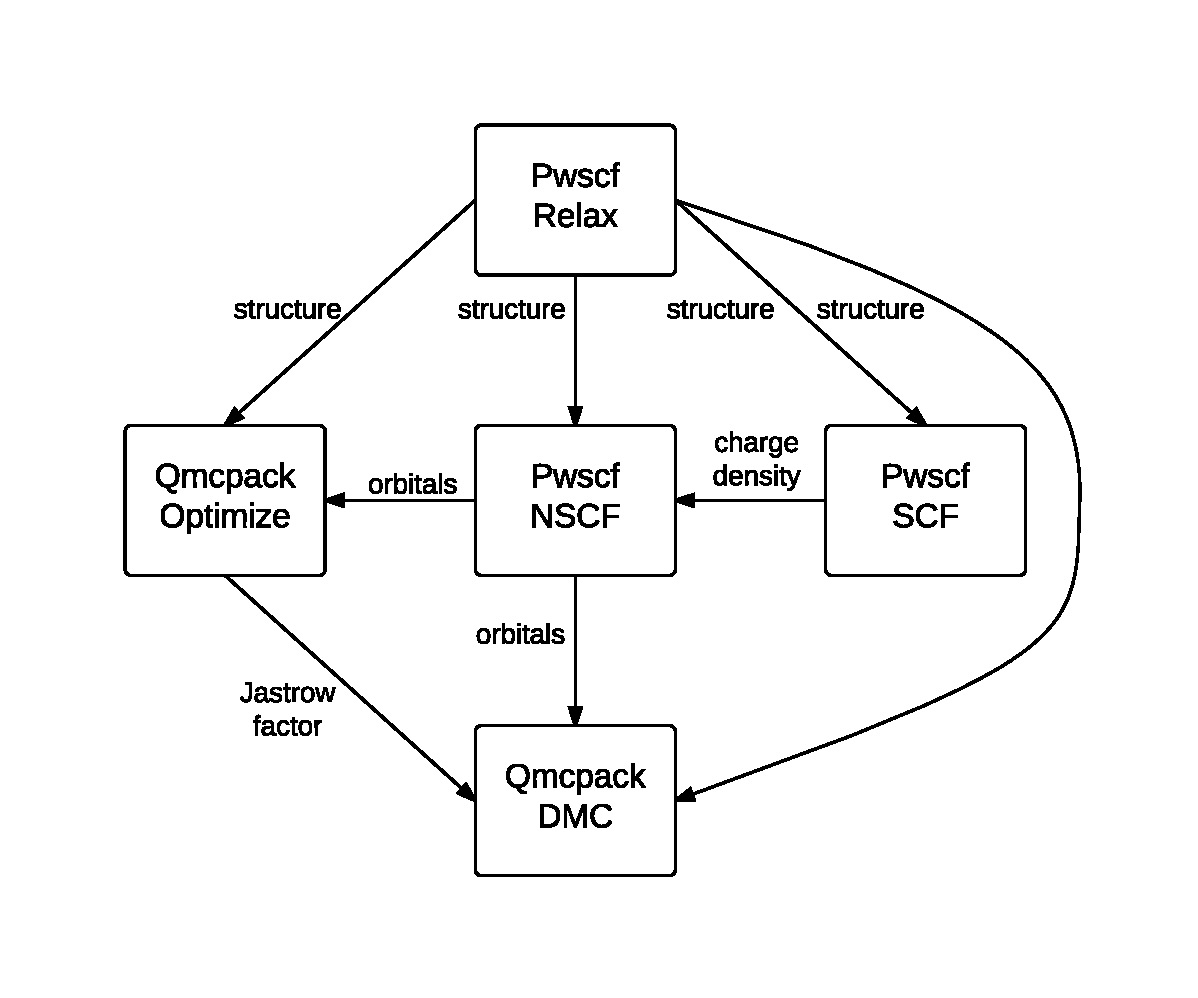

Fig. 1 An example Nexus workflow/cascade involving QMCPACK and PWSCF. The arrows and labels denote the flow of information between the simulation runs.

Composing workflows from simulation objects

Simulation workflows are created by specifying the data dependencies between simulation runs. An example workflow is shown in Fig. 1. In this case, a single relaxation calculation performed with PWSCF is providing a relaxed structure to each of the subsequent simulations. PWSCF is used to create a converged charge density (SCF) and then orbitals at specific k-points (NSCF). These orbitals are used by each of the two QMCPACK runs; the first optimization run provides a Jastrow factor to the final DMC run.

Below is an example of how this workflow can be created with Nexus. Most

keywords to the generate functions have been omitted for brevity.

The conv step listed below is implicit in Fig. 1.

relax = generate_pwscf(

...

)

scf = generate_pwscf(

dependencies = (relax,'structure'),

...

)

nscf = generate_pwscf(

dependencies = [(relax,'structure' ),

(scf ,'charge_density')],

...

)

conv = generate_pw2qmcpack(

dependencies = (nscf ,'orbitals' ),

...

)

opt = generate_qmcpack(

dependencies = [(relax,'structure'),

(conv ,'orbitals' )],

...

)

dmc = generate_qmcpack(

dependencies = [(relax,'structure'),

(conv ,'orbitals' ),

(opt ,'jastrow' )],

...

)

As suggested at the beginning of this section, workflow composition logically breaks into two parts: simulation generation and workflow dependency specification. This type of breakup can also be performed explicitly within a Nexus user script, if desired:

# simulation generation

relax = generate_pwscf(...)

scf = generate_pwscf(...)

nscf = generate_pwscf(...)

conv = generate_pw2qmcpack(...)

opt = generate_qmcpack(...)

dmc = generate_qmcpack(...)

# workflow dependency specification

scf.depends(relax,'structure')

nscf.depends((relax,'structure' ),

(scf ,'charge_density'))

conv.depends(nscf ,'orbitals' )

opt.depends((relax,'structure'),

(conv ,'orbitals' ))

dmc.depends((relax,'structure'),

(conv ,'orbitals' ),

(opt ,'jastrow' ))

More complicated workflows or scans over parameters of interest can be created with for loops and if-else logic constructs. This is fairly straightforward to accomplish because any keyword input can given a Python variable instead of a constant, as is mostly the case in the brief examples above.

Workflow execution

Simulation jobs are actually executed when the corresponding simulation

objects are passed to the run_project function. Within the

run_project function, most of the workflow management operations

unique to Nexus are actually performed. The details of the management

process is not the purpose of this section. This process is discussed in

context in the Complete Examples walkthroughs.

The run_project function can be invoked in a couple of ways. The

most straightforward is simply to provide all simulation objects

directly as arguments to this function:

run_project(relax,scf,nscf,opt,dmc)

When complex workflows are being created (e.g. when the generate

function appear in for loops and if statements), it is generally

more convenient to accumulate a list of simulation objects and then pass

the list to run_project as follows:

sims = []

relax = generate_pwscf(...)

sims.append(relax)

scf = generate_pwscf(...)

sims.append(scf)

nscf = generate_pwscf(...)

sims.append(nscf)

conv = generate_pw2qmcpack(...)

sims.append(conv)

opt = generate_qmcpack(...)

sims.append(opt)

dmc = generate_qmcpack(...)

sims.append(dmc)

run_project(sims)

When the run_project function returns, all simulation runs should be

finished.

Limiting the number of submitted jobs

Nexus will submit all eligible jobs at the same time unless told otherwise. This can be a large number when many calculations are present within the same project, e.g. various geometries or twists. While this is fine on local resources, it might break the rules at computing centers such as ALCF where only 20 jobs can be submitted at the same time. In such cases, it is possible to specify the the size of the queue in Nexus to avoid monopolizing the resources.

from nexus import get_machine

theta = get_machine('theta')

theta.queue_size = 10

In this case, Nexus will never submit more than 10 jobs at a time, even if more jobs are ready to be submitted, or resources on the local machine are available.

Having the option of limiting the number of jobs running at the same time can be useful even on local workstations (to avoid taking over all the available resources). In such a case, a simpler strategy is possible by claiming fewer available cores in settings, e.g. machine=’ws8’ vs ‘ws4’ vs ‘ws2’ etc.

Data analysis

Following the call to run_project, the user can perform data

analysis tasks, if desired, as the analyzer object associated with each

simulation contains a collection of post-processed output data rendered

in numeric form (ints, floats, numpy arrays) and stored in a structured

format. An interactive example for QMCPACK data analysis is shown below.

Note that all analysis objects are interactively browsable in a similar

manner.

>>> qa=dmc.load_analyzer_image()

>>> qa.qmc

0 VmcAnalyzer

1 DmcAnalyzer

2 DmcAnalyzer

>>> qa.qmc[2]

dmc DmcDatAnalyzer

info QAinformation

scalars ScalarsDatAnalyzer

scalars_hdf ScalarsHDFAnalyzer

>>> qa.qmc[2].scalars_hdf

Coulomb obj

ElecElec obj

Kinetic obj

LocalEnergy obj

LocalEnergy_sq obj

LocalPotential obj

data QAHDFdata

>>> print qa.qmc[2].scalars_hdf.LocalEnergy

error = 0.0201256357883

kappa = 12.5422841447

mean = -75.0484800012

sample_variance = 0.00645881103012

variance = 0.850521272106